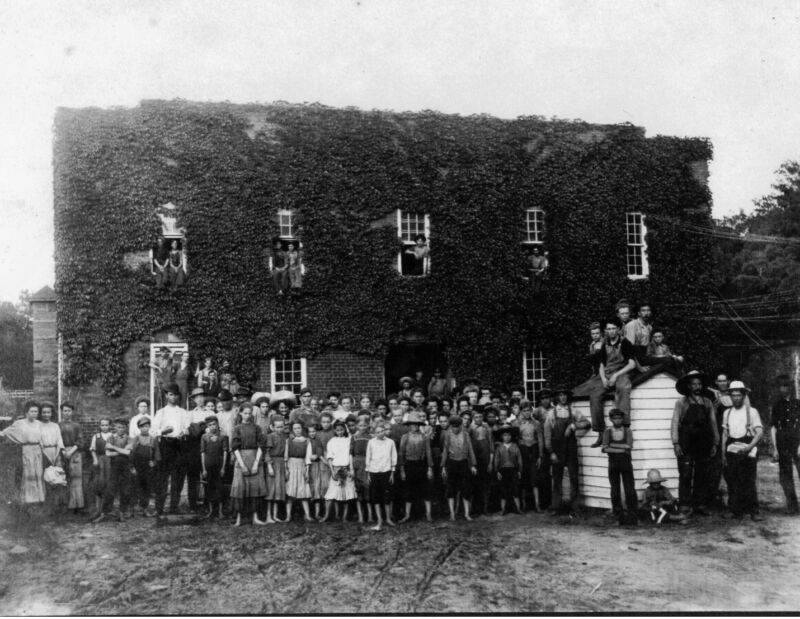

Men, women, and children—both enslaved and free—worked at the Athens Factory

Prior to the Civil War, men, women, and children—both enslaved and free—worked within the walls of the Athens Factory in the same spaces that the UGA School of Social Work classrooms and offices occupy now. After the Civil War, the mill’s “operatives,” as the workers were known, were white men, women, and children (Gagnon, 2012).

In 1859, the Bank of Athens featured women at factory looms on the $20 note.

Image courtesy of Gary Doster

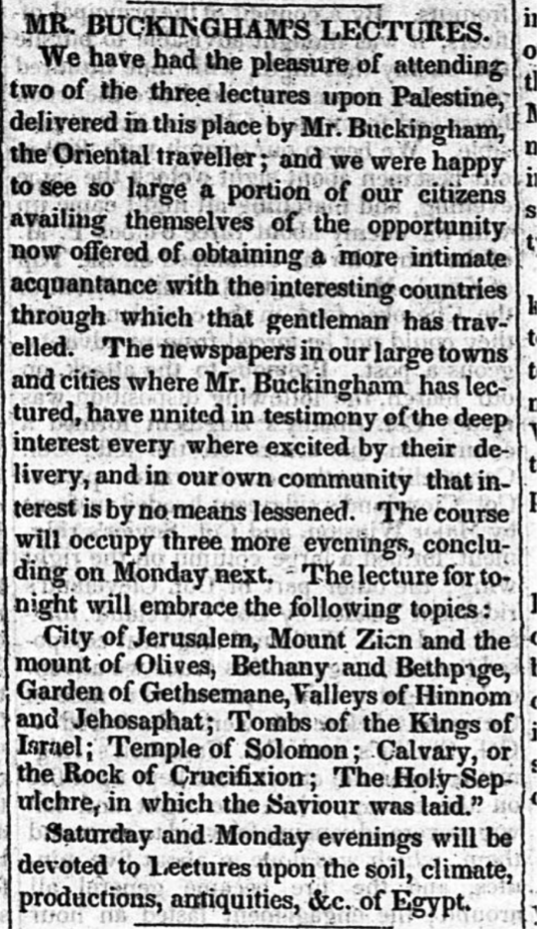

Editorial, The Southern Banner, June 28, 1839, Georgia Historic Newspapers, Digital Library of Georgia

The British world traveler and lecturer James Silk Buckingham visited Athens in 1839. Later, he described the relations between the enslaved Black and free white workforce at an Athens cotton mill in the travelogue of his adventure, The Slave States of America (1942).

I visited one of these, and ascertained that the other two were very similar to it in size and operations. In each of them there are employed from 80 to 100 persons, and about an equal number of white and black. In one of them, the blacks are the property of the mill-owner, but in the other two they are the slaves of planters, hired out at monthly wages to work in the factory. There is no difficulty among them on account of color, the white girls working in the same room and at the same loom with the black girls; and boys of each color, as well as men and women, working together.

After the Civil War, it was common for whole extended families to work in the mill and live in housing that was owned by the Athens Manufacturing Company. If you look closely at this 1914 image of an Athens Factory mill village, you can see the Athens Factory and the old dye house that used to sit next to it. Across the North Oconee River, the white building with the mansard roof (also owned by the Athens Manufacturing Company) served as both a flour mill and an electric company during the latter part of the 19th century.

Close-up of Athens Factory operative housing. From “Panoramic view of Athens,” 1914.

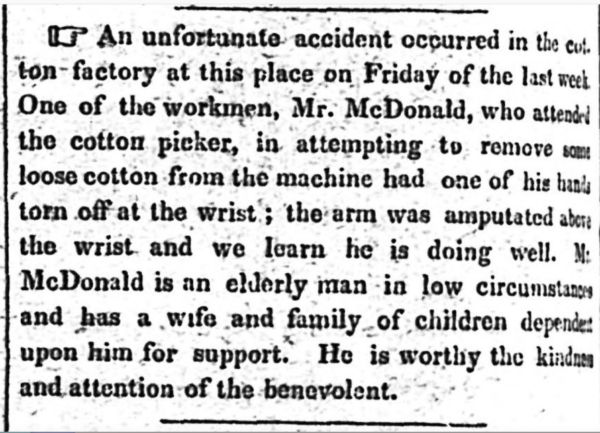

Working at the Mill was Difficult and Dangerous

Working at the mill was difficult, unhealthy and dangerous work. Injuries were reported, limbs were lost, and both observers and mill workers commented on the risks.

On September 6th, 1834—less than one year after the factory began operation—The Southern Banner reported a serious accident at the mill. According to the newspaper, Mr. McDonald was “doing well” after having his hand “torn off at the wrist” while attempting to remove loose cotton from a machine. Mr. McDonald was described as “an elderly man in low circumstances [who had] a wife and family of children dependent on him for support.” Reaching out to their readers, the newspaper let their readers know that the family would be “worthy the kindness and attention of the benevolent.” Whether the owners of the Athens Factory also planned to be “benevolent” to the family was not reported.

Editorial, The Southern Banner, September 6, 1834, Georgia Historic Newspapers, Digital Library of Georgia

James Silk Buckingham, a British chronicler who visited an Athens cotton mill in 1839, was very critical of the working conditions he found in the factory. He wrote:

[The mill’s white workers] looked miserably pale and unhealthy; and they are said to be very short-lived, the first symptoms of fevers and dysenteries in the autumn appearing chiefly among them at the factories, and sweeping numbers of them off by death. Under the most favourable circumstances, I think the Factory system detrimental to health, morals, and social happiness; but in its infant state as it is here, with unavoidable confinement in a heated temperature, and with unwholesome associations, it is much worse (Slave States of America, page 113).

In 1914, mill work was still dangerous according to 5th-grader Ben Boles. As Ben wrote to The Athens Daily Herald about his days on of Athens cotton factories, “while we often have fun sometimes, it is dangerous work if you are not careful.”

After the end of slavery, free Black workers were employed by the Company as manual laborers. In 1936, Robert Shepherd, then 91-years-old, gave an interview to Grace McCune of the Federal Writers’ Project at his home at 386 Arch Street in East Athens. McCune’s report on their conversation details Shepherd’s experiences as an enslaved person in Oglethorpe County and his life in Athens after Emancipation. McCune relates (in her version of Shepherd’s voice) that Shepherd worked for Robert Bloomfield in the 1870s or 1880s after the Athens Manufacturing Company had expanded to comprise both the Athens Factory and the Check Mill (now UGA’s Chicopee Building). Shepherd speaks of being assigned a variety of jobs inside the mill, around the yard, and on the boat that used to transport cotton and cloth up and down the North Oconee River between the two mills.

In 1939, another retired mill worker, 67-year-old Henry Hunt, also gave an interview to the Federal Writer’s project. Mr. Hunt, a white millworker whose parents, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and siblings all worked for the Athens Manufacturing Company beginning before the Civil War and lasting beyond his birth in 1871 until at least 1900. Mr. Hunt was born in a house that belonged to the company and he remembers that the company president Robert Bloomfield knew all the mill children’s names, built St. Mary’s church for them, and closed the mill down during watermelon season “to give us the opportunity to enjoy eating watermelons.”

Though he had many good memories, he described the conditions in the mill very much as Buckingham had described them a century before:

In my young days, the life of a mill worker wasn’t very long. The close confinement, long hours, lint and dust that they had to breathe, all worked together to shorten their lives. Most everybody had a cough. I’ve had this cough ever since I can remember. Men and women all had sallow complexions, and the younger folks didn’t have any color in their cheeks either. The mills of those days didn’t have any way of controlling the dust and lint, and the air we breathed was dry and stale…And another thing; in those days sanitary conditions were mighty bad sometimes. That was because so many lived crowded together in the same house, breathing the same air that came from the lungs of the sick ones.

Mr. Hunt began doing odd jobs for Mr. Bloomfield as a young boy. He stated, “To make a good textile worker you had to start young, say around the age of eight,” and Mr. Hunt was working full time before his 15th birthday. Over the course of his years with the company, he worked in both mills operated by the Athens Manufacturing Company: the Athens Factory on Williams Street and the “Check Mill,” as UGA’s Chicopee Building was then known.

Doffer boys in Bibb Mill #1, Macon, Ga. Location: Macon, Georgia.

Photo by Lewis Wickes Hine

Cite this Article

McPherson, J. (2024, January 6). Working at the mill. Complex Cloth. https://complexcloth.org/working-at-the-mill/

Sources

Buckingham, J. S. (1842). Slave states of America. Fisher, Son.

Federal Writers’ Project. (1936). Federal Writers’ Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 4, Part 3, Kendricks-Styles, Robert Shepherd, 246-263. Retrieved from Library of Congress, Manuscript/Mixed Material. https://www.loc.gov/item/mesn043/

Gagnon, M.J. (2012) Transition to an Industrial South:Athens, Georgia 1830–1870, aton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press.

The Athens Daily Herald (1914) A letter from the Fifth Grade, 10 November, https://localhost:8000/lccn/sn88054118/1914-11-10/ed-1/seq-7/print/image_668x817_from_0,0_to_3805,4649/

The Southern Banner (1834) An unfortunate accident, 6 September, https://localhost:8000/lccn/sn82014069/1834-09-06/ed-1/seq-2/print/image_609x817_from_0,1_to_6069,8139/.