The Athens Factory investors

envisioned an Enslaved Workforce

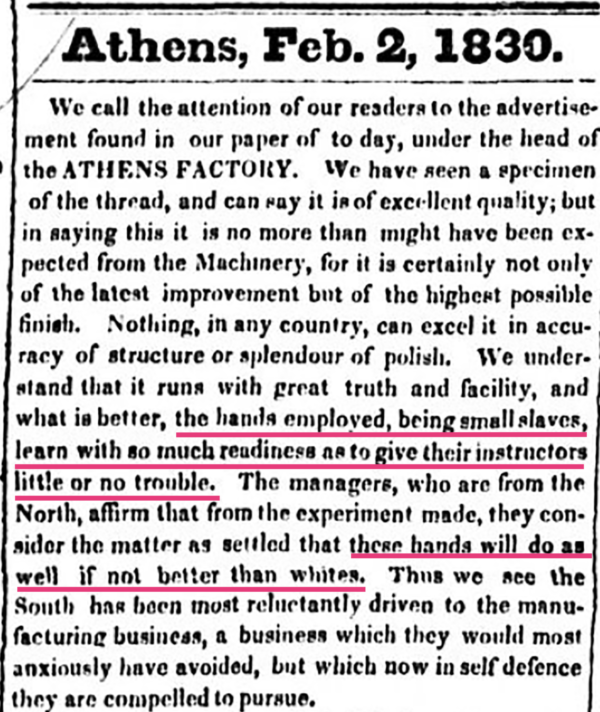

Editorial, The Athenian, February 2, 1830, Georgia Historic Newspapers, Digital Library of Georgia

When the Athens Factory opened its doors in 1833, it was the first cotton mill in the city of Athens and one of the first two cotton mills south of the Potomac River. Prior to 1830, nearly all of Georgia’s cotton was sent north or overseas to be milled into fabric, but rising tariffs encouraged southern landowners and enslavers to consider milling cotton nearer to home (Gagnon, Transition, 17-20).

As the men who built Athens Factory contemplated building cotton mills in the South, they imagined that an enslaved labor force would operate the factory looms and spindles. They imagined a Southern manufacturing process whose laborers (unlike those in the North) could “neither strike nor quit” (Gagnon, Transition, 28, 48-49).

The Athenian—our local newspaper— was bullish on this use of enslaved labor for factory work, asserting that “the slave hands…learn with so much readiness as to give their instructors no trouble” and concluded that “these hands will do as well as, if not better than, whites.”

James Silk Buckingham, the British chronicler who visited Athens in 1839, explains that even though enslaved and white laborers were “paid” the same wages (enslaved workers’ wages were “handed over to the owners”), use of enslaved labor was ultimately “dearer than that of the whites” because the manufacturers were also required to provide rented enslaved workers with full board and housing (“the negroes…stay at the mill, when their master’s plantation is far off; pp. 112-113.) Even so, the Athens Manufacturing Company paid city fees suggesting that they continued to rent at least occasional enslaved labor throughout the antebellum period (Coulter, “Slavery and Freedom,” p. 270). Over time, though, as Michael Gagnon writes in his monograph on early industrial Athens, “slaves simply became too valuable to work in factories in the Deep South, except for jobs that whites could not be induced to take” (p. 52), and by 1850, white women and girls were performing “most of the labor in textile mills” (p. 56).

This detail from the foreground of George Cooke’s View of Athens from Carr’s Hill, highlights the role on an enslaved man in managing the transportation of bales of cotton.

The Athens Factory Directly Participated in the Slavery-based Economy

The Athens Manufacturing Company participated directly in slavery from the time of its founding until at least 1863. The founders and investors in the company were enslavers themselves and many owned agricultural lands that were cultivated by enslaved laborers. The company itself also bought, sold, and rented enslaved people who likely lived on the factory grounds.

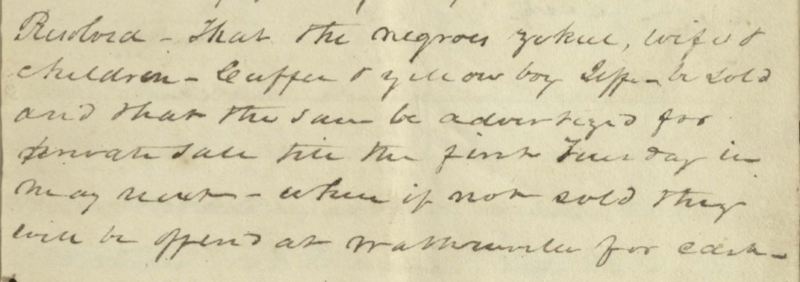

In June of 1836, “seven negroes”—Bob, Cuffee, and Charles, along with Ezekiel and Dinah and their two children—are listed alongside the other assets of the company, including “lands, water privileges, mills, factory buildings…smith tools, wagon and team and the stock of wool.” Many of these same individuals appear again in the company minutes in May 1843 and February 1844, when the stockholders resolved to sell Cuffee, Ezekiel, and Ezekiel’s family members, along with another person known only as “yellow boy,” in order to pay off company debt. During the Civil War in 1863, the company sold the last of their human property.

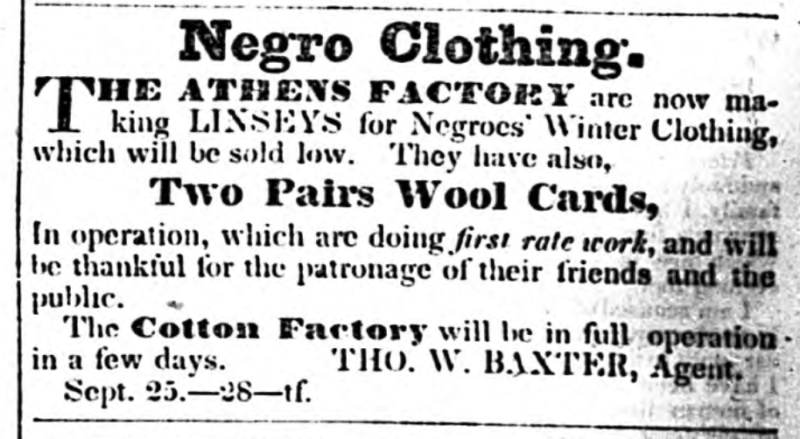

Advertisement, The Southern Banner, October 23, 1840, Georgia Historic Newspapers, Digital Library of Georgia

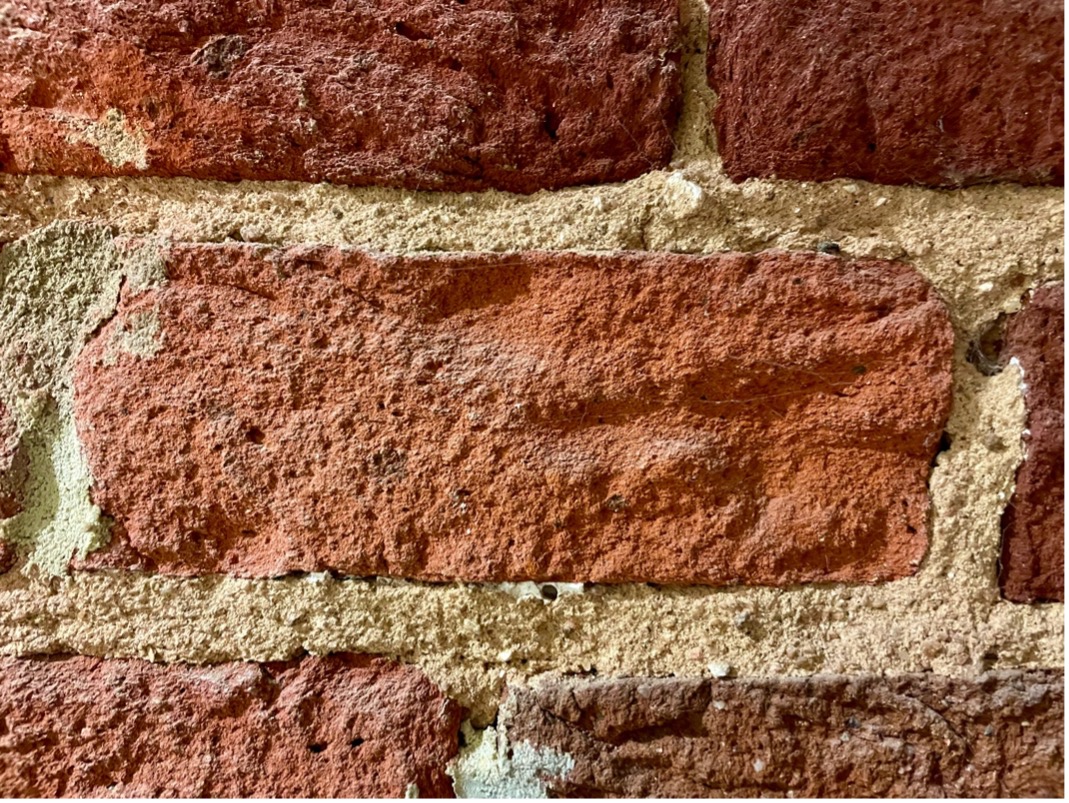

Many of the bricks that make up the School of Social Work walls date from 1857 or before. The bricks—formed by hand—were almost certainly made by enslaved laborers. If you look closely, you can see the marks of their hands and fingers in the clay.

Photographs courtesy of Jane McPherson

Cite this Article

Cite this Article

Buckingham, J.S. (1842), The Slave States of America, 112-113. Fisher, Son.