Child Labor powered Georgia’s Cotton Mills

Many changes came to the Athens Manufacturing Company during its first century of operations (1832-1932), but child labor was a constant. Prior to the Civil War when spinning and weaving operations were located at the Athens Factory, both enslaved and free children worked on the factory’s spinners and looms, doing the many tasks that their small hands could master. After the Civil War, children worked in both the Athens Factory, where thread was spun, and in the Check Factory, where thread was woven into cloth.

"Little Spinner in a Georgia Cotton Mill." Photograph (1909) by Lewis Wickes Hine

Athens-Clarke Public Library Heritage Room

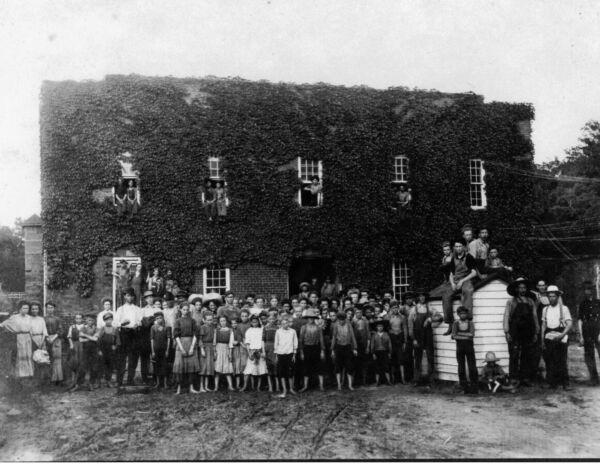

Though no photos of child workers at Athens Manufacturing Company have yet been located, there is one local photo (circa 1910) of young millworkers taken at Whitehall. The Whitehall Mill, located near the southern end of Milledge Avenue, opened in 1830 and was the first cotton mill in Georgia.

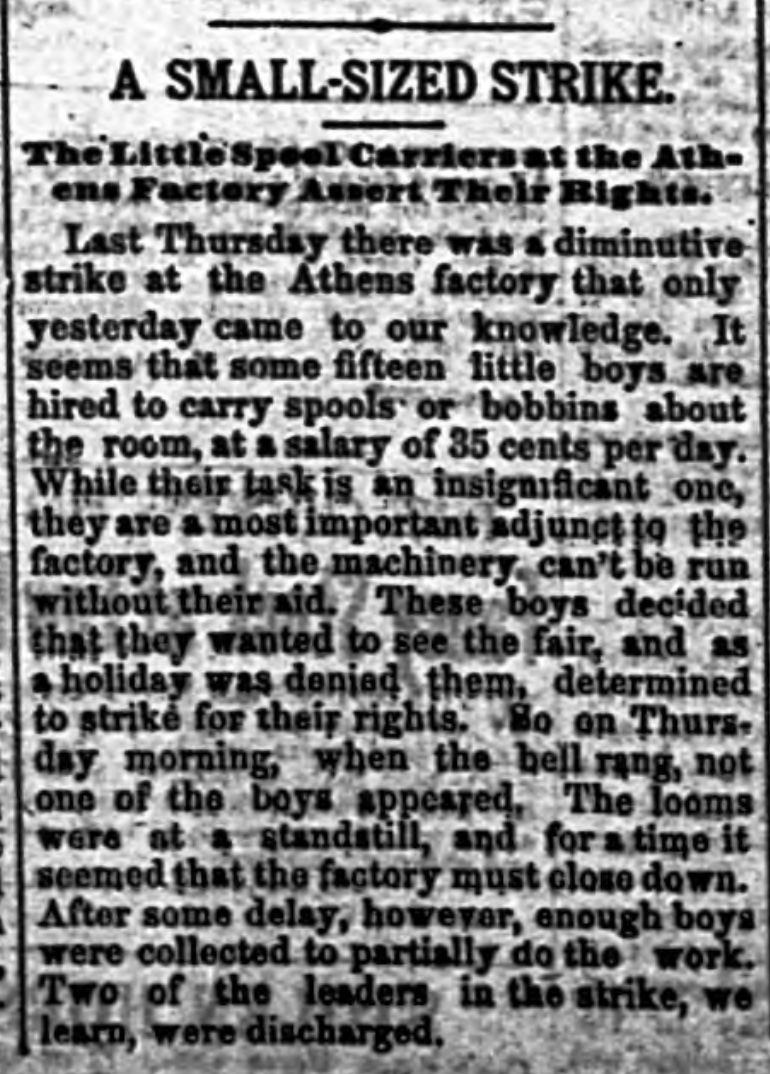

Work in the mill was hard and children were expected to work from morning until night like the adult employees. In 1886 when the fair came to Athens, there was a move among many local employers to close their businesses for half a day so that “all the boys [would have] a chance to see the fair.”

Editorial, The Daily Banner-Watchman, November 11, 1886, Georgia Historic Newspapers, Digital Library of Georgia

Editorial, The Weekly Banner-Watchman, November 23, 1886, Georgia Historic Newspapers, Digital Library of Georgia

Fairs were wonderful and much-anticipated events when they came to Athens. The Wheat and Oat Fair came to Athens for three consecutive years (1901-1903) in the early part of the 20th-century. The bobbin boys would have hoped to attend a different fair, but the spectacle would have been similarly glorious.

Thomas, William W. photographs, Hargrett Library, UGA

The Athens Manufacturing Company didn’t close for the fair, so 15 small boys “hired to carry spools or bobbins” went out on strike. The Weekly Banner-Watchman reported that “the boys decided that they want to see the fair, and as a holiday was denied them, determined to strike for their rights.” The strike put the looms at a standstill and two leaders of the strike were later discharged.

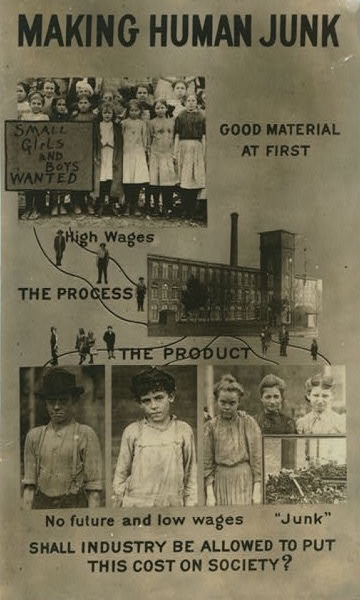

Child labor was common, but it was also controversial. Reformers believed that putting children to work in factories turned healthy young people into “human junk.” Child labor laws in Georgia were among the least protective in the nation, and by 1911, Georgia was the only state still allowing children under twelve to be employed in factory work, and the only one allowing a sixty-six-hour work week for children (Jones, 1965). Lewis Hine (1874-1940) became the photographer for the National Child Labor Committee in 1908, and his portraits of young millworkers (including the portraits of Georgia kids on this page) turned many people against the practice.

Lewis Hines’ exhibit panel, “Making Human Junk,” was produced for the National Child Labor Committee around 1913 or 1914.

Athens Women’s Club supported providing education to the white children working in the mills. In Georgia, mill work was generally restricted to white families prior to the 1960s.

Editorial, The Weekly Banner, November 9, 1906, Georgia Historic Newspapers, Digital Library of Georgia

In Athens, members of the (all white) Athens Women’s Club joined the fight against child labor and for providing education to millworker kids. According to Mary Ann Lipscomb’s 1908 address to the Georgia Federation of Women’s Clubs, local women were pushing for laws “that would free our children from the slavery of the mill,” against the staunch and successful efforts of the “mill men” who “thwarted [their] efforts.” Mrs. Lipscomb’s address put this advocacy in both humanitarian and white supremacist terms as she spoke of children who had “in their veins the best blood of many nations” and continued, “it will be comparatively an easy task to lift them back to a higher plane, for there is no stronger law than that of heredity.”

With support from the Athens Women’s Club, the East Athens Night School opened in Athens in 1897. Night schools for mill kids operated in Athens through the 1920s.

In 1994, Georgia Public Broadcasting interviewed several older adults who went to work in the mills as children. Some of them chose to work 6 hours per day (“part-time”) so they could attend school, rather than putting in the standard 12-hour day.

"Doffer boys in a Georgia Cotton Mill." Photograph (1909) by Lewis Wickes Hine.